SC25 info

As of the publication of this post the application for UCSD’s 2025 team has opened. For those applying the deadline is April 20th and status updates will be sent out the following week. More details are listed on the application page.

On top of participating as a team in the student cluster competition, the Supercomputing convergence offers opportunities for students to attend the convergence as a Student Volunteer and Scinet Volunteer. Note that the time commitment for student volunteers is the week of the conference and for SCInet volunteers being two weeks the week of the conference and the week preceding the conference. For those applying if you’re from UCSD and are accepted as volunteers for either program please reach out to Mary Thomas, so we have sufficient lead time to allocate travel funding support.

Student Cluster Competition 2024 postmortem

Competition Details

TLDR:

- All software and hardware we used must be publicly available at the start of the competition.

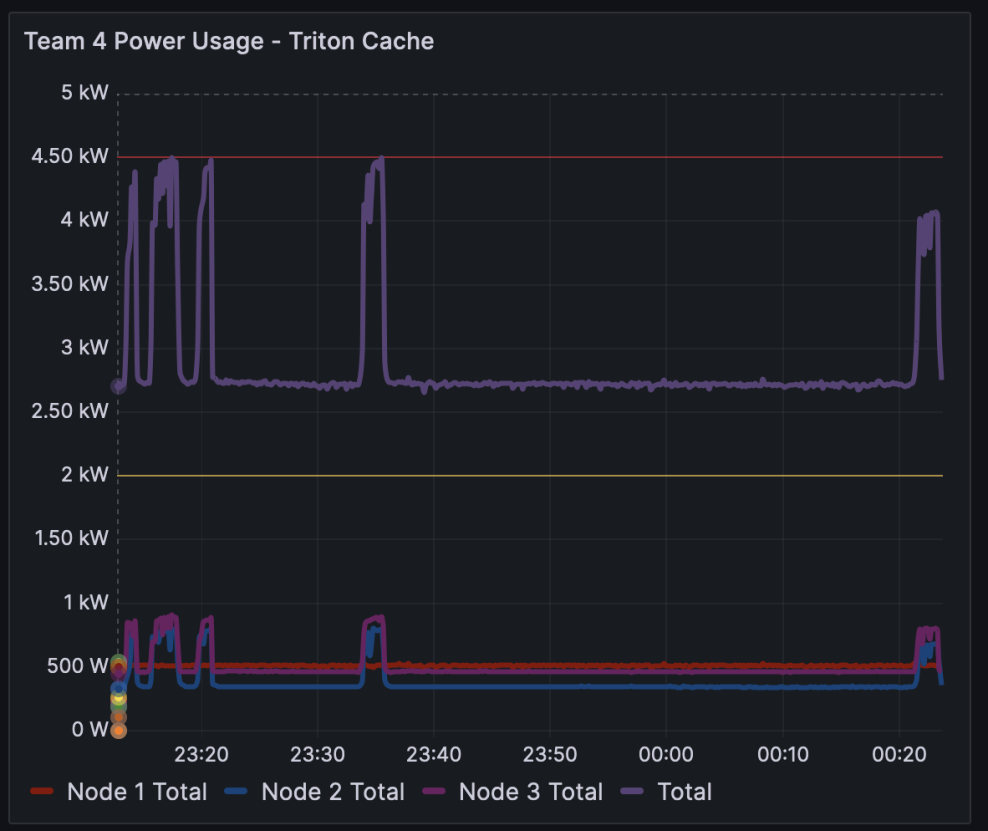

- 4.5 kW limit for entire cluster, 2 kW limit per node

- Benchmarks are: HPL, MLPERF inference, and a mystery benchmark revealed at the start of the benchmarking period.

- Applications are: NAMD, ICON, Reproducibility (data flow lifecycle analysis tool DataLife), and a mystery application revealed at the start of application period

- NAMD is a parallelized molecular dynamics simulation software for large biomecular systems.

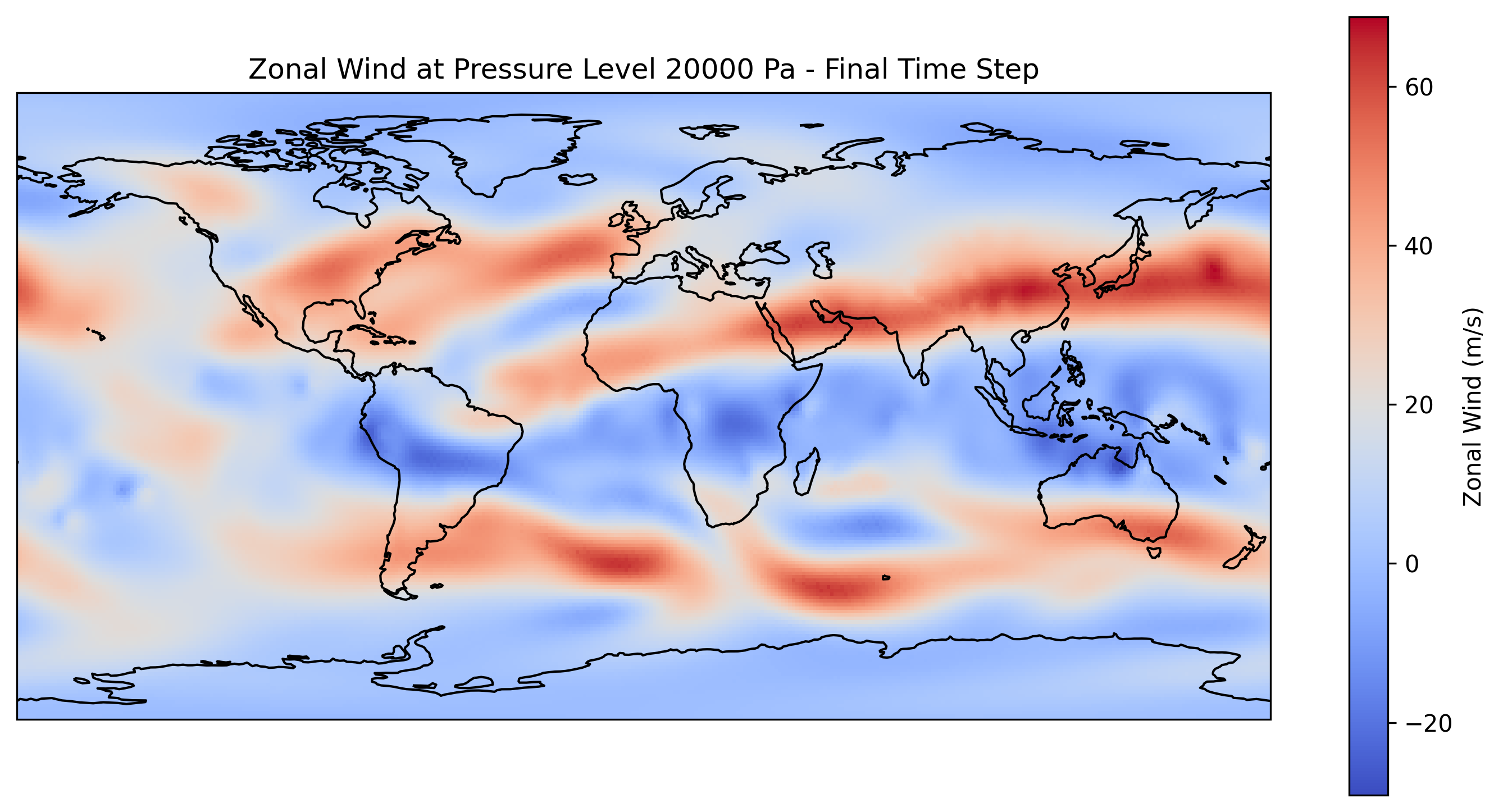

- Icosahedral Nonhydrostatic, or ICON, is a complex weather modeling application that is part of Germany’s DWD weather monitoring service, part of NOAA’s (a US weather agency) ensemble model that predicts global weather, and a tool used by amateur hurricane trackers. Although a GPU port exists, ICON is typically compiled for CPU runs and its data-heavy nature means that it streses a system’s IO.

- You must try to achiece the best scores for benchmarks, applications, systems, and certain other areas.

- Benchmarking period 8am-5pm. Application period is the next 48 hours. No external help.

You can read for further details on the SCC SC24 page. Team introductions are on the page as well. If you are interested in the history of the program, you may also see the official Student Cluster Competition site.

System Specifications

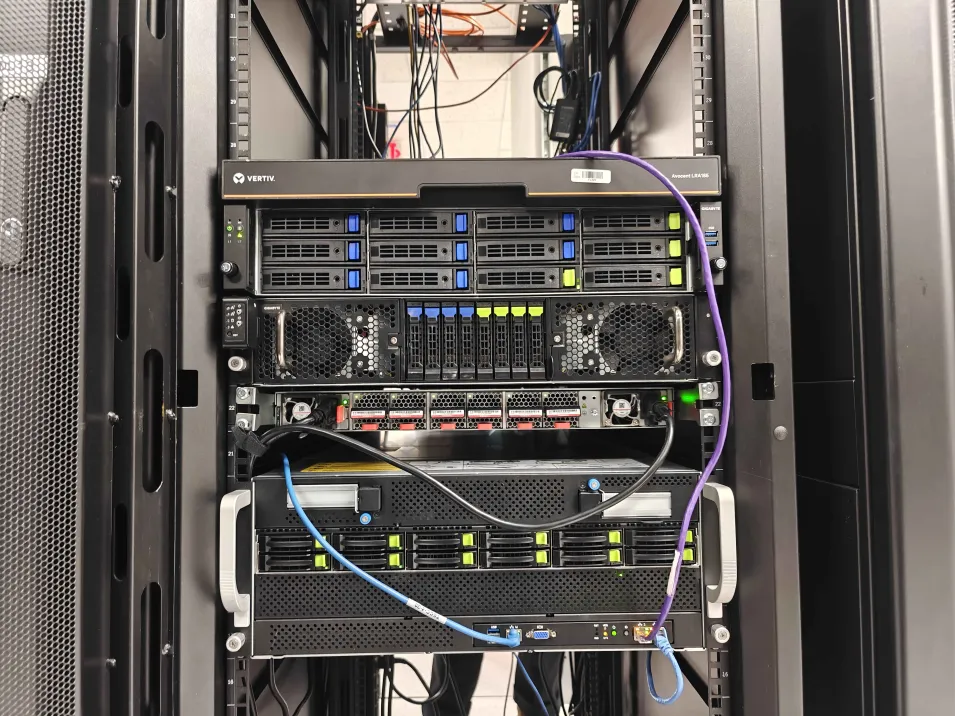

A diagram of our final system, Ocean Vista:

Our system for 2024 is very similar to our system from scc23. They both consist of 3 nodes: 2 GPU node, 1 CPU node with Liqid IO cards. They both have a ROCm stack of Genoa EPYC processors and CDNA 2. However, this year our cluster is distinguished by it’s heterogenous nature. Let’s look at parts and vendors list:

| Parts | Vendor |

|---|---|

| 3x 1meter copper cables from | Pivotal Optics |

| 3x Broadcom 400bps NICs | Broadcom, but Micas Networks were the middle men |

| 1 400gbps Switch | Micas Networks |

| R283-Z93-AAF1 (Server) + AMD CPUs | Applied Data Systems + Gigabyte |

| G293-Z22-AAP1 (Server) + AMD CPUs | Aeon Computing + Gigabyte |

| G493-ZB2-AAP1 (Server) + AMD CPUs | International Computer Concepts (ICC-USA) + Gigabyte |

| 2x4500 IO Acc. “Honey Badger” | LIQID |

| 4x MI210s | HPE (Michael Woodacre) |

| 4x MI210s | AMD |

| 4x Infinity Fabric Links (2 used) | AMD |

| 8(+5)x GPU power connectors | Aeon/ICC-USA |

Here is the diagram matching the hardware with the source of vendor:

How did we get here? It was not easy. We had a lot of help. A lot of help.

Besides lending the team hardware, we received generous financial donations from Micas Networks and Intel, as well as the mentoring and help from our company sponsors and the faculty and staff from SDSC, UCSD, and the CSE department.

Preparing for Benchmarks and Applications

Early on, we divided out work into teams with a few overlapping responsibilities. In this division of teams we also included students from our home team, another number of students who helped prepare and worked on the tasks with the travel team but ultimately stayed at our institution during the conference.

During the summer we had weekly meetings to sync up on our progress. Throughout these weeks we were working. Working on our tasks on our club resources. Through one of our members, we were able to get access to MI210s in an AMD research cluster. Through SDSC, the Expanse supercomputer. And through the club itself, a few older servers. Once in a while, we would meet with our mentors to ask them for advice or help regarding certain technical and nontechnical issues we would come accross.

Our goals were to familiarize with the benchmarks and applications, as well as practice our HPC skills. There were also certain stages of the competition application we would have to submit every couple of weeks: final team submission, final poster, and a final architecture. And while we were working, we were also speccing out what we wanted from our cluster with our hardware vendor(s).

NAMD

We spent summer understanding how NAMD and molecular dyanmics in general worked, by running simulations from the user guide and following online tutorials. We also tested a variety of NAMD builds; NAMD as a software was built to work with the Charm++ message-passing parallel language, and Charm++ setup was dependent on the underlying network layer setup we wanted to use (netlrts, Infiniband, MPI). A really important thing to note about NAMD was that the developers had just released version 3.0, which introduced a new “GPU-resident” mode. NAMD’s GPU-resident mode offloaded all calculations including integration calculations to the GPU, making simulations much faster compared to the CPU and the weaker GPU-offload mode available. However, GPU-resident mode could only run on a single node. We realized that these variations would be key to maximizing performance on our cluster.

In the fall, we focused on running the publicly available NAMD benchmarks and toggling the different command line parameters and configuaration parameters to maximize performance on the AMD server available to us. We also had invaluable mentor support; Andy Goetz helped us understand how MD works, and Julio Maia, a researcher at AMD who was one of the NAMD developers, gave us crucial advice on different types of NAMD simulations and worked with us to resolve issues in NAMD’s source code due to incompatibility with AMD hardware.

When we finally had access to our cluster the week before shipping it out (more on that later), there were a new slew of problems. For some reason NAMD would not work with the netlrts installation of Charm++; even though the nodes were able to connect to each other via ssh protocol, Charm++ was not able to establish that connection. We switched over to the MPI version, but were unable to get MPI working until right before shipping the cluster.

ICON

Throughout the summer and fall, it was a massive struggle for our team to compile ICON, since documentation was limited to a few custom architectures and the complex nature of the program meant that a lot of testing and debugging was required to find the right set of compile parameters for our architecture. The complex compile process required iterating through build scripts and making sure all of the required dependencies were able to talk to each other. The changing nature of our cluster in certain weeks meant that there were occasionally changinges to our linker flags and other variables. Having Spack set up made a huge difference in this effort. Spack allowed us to more easily manage the dependencies, installations, and making sure that everything was using a supported version.

ICON required relentless debugging and iteration. Being transparent with teammates about problems, deadlines, and resource usage kept us aligned under pressure. Having the support of our home team and mentors was helpful at this stage, providing multiple perspectives and ensuring someone was always trying something new to make the best of a difficult situation.

After many trials, we settled on a CPU-only run for ICON, which freed up the GPUs for other applications. This ensured that we would be able to give our other applications, which had been more successful in our testing, more resources and time to run, while trying our best with ICON even though we knew it would be a struggle.

HPL

Over the summer, we focused on understanding how HPL (High-Performance Linpack) works and how different configurations affect performance. HPL is a benchmark designed to measure the floating-point computing power of a system, particularly for ranking in the Top500 list. We started by running small-scale HPL tests using default configurations and gradually explored tuning parameters such as block size (NB), process grid dimensions (P and Q), and memory allocation strategies to maximize performance.

A key aspect of our preparation was experimenting with different deployment methods. We compared running HPL natively on the system versus using containerized solutions such as Singularity, Spack, and Docker. Each method had trade-offs—while Spack provided a convenient way to build optimized versions of HPL and its dependencies, Singularity allowed us to maintain performance consistency across different environments, and Docker offered ease of reproducibility. Understanding these differences was crucial for determining the best approach for our cluster.

In the fall, we focused on optimizing HPL for the AMD server available to us. We tested different BLAS (Basic Linear Algebra Subprograms) libraries. Throughout this process, we had support from researchers who had experience benchmarking HPC systems, which helped us fine-tune our approach.

When we finally gained access to our cluster the week before shipping, we faced new challenges. Setting up MPI correctly was critical for HPL to scale across multiple nodes, and we had to troubleshoot issues with network communication. Docker provided a reliable way to deploy HPL across the cluster, but we also tested Spack to see if we could further optimize the software stack. In the end, after resolving MPI configuration issues and finalizing the optimal HPL parameters, we were able to get strong performance numbers just in time before shipping.

Sourcing Hardware (a major challenge)

The earliest hardware we got was the 32 Port 400Gb Switch from Micas Networks. Our relationship with the company started with the SCC23 team at last years conference. For this competition year, Micas Networks was one of our essential supporters. They generously lent us their hardware since May, and this support pushed our team to really reach the 400Gb bandwidth speeds despite having a small cluster.

Over the summer we were told by our primary system vendor that the hardware we’ve been speccing out was unattainable due to a lack of support. This upsetting news came in late July and quickly became a source of stress. We were late into the cycle, with only an idea of what we needed, and no finalized physical means of compute.

The meetings from then forward consisted of scouting out alternatives with SDSC mentors, contacts, suppliers, etcetera. This was a long process, and to fail here would mean that we would have to resort to a system discarded by surplus—or worse, not have a system. We spoke with local vendors about systems. Our own sponsors looked at their contacts. And the sponsor network really grew. It was a lot of emails, calls, and meetings. But as long as we kept calling, kept emailing, and kept taking one step at a time or one component at a time, we were going to build our cluster.

The first system integrator was Applied Data Systems. They showed support by going through the effort of driving a node down to SDSC and meeting the students. This system was to be loaned for a couple months, and we carried and racked the system into our personal club room. This was the first final machine we started to work on, “Percy” (though early on we dubbed it Ryan after our sponsor). This node, however, would not be able to accomodate MI210 GPUs due to the slots of the FHFL 2PCIe width slots.

The second system came from Aeon Computing. This machine came a couple weeks later. Aeon provided us with the second system that could fit 4 pairs of MI210s, which by coincidence as also a Gigabyte node. By this time we had begun moving our machines into the datacenter, a privilege provided by SDSC that most students don’t get. We could at least test CPU only runs, as well as basic sysadmin and network configurations.

At the same time we were trying to retrieve necessary peripherals. Because even with our systems starting to be put together, we really couldn’t call ourselves an HPC cluster. Support from AMD came from a promise of Infinity Fabric Links and 4xMI210s, half of how many we needed. And Micas Networks had arranged us with 3 400Gb NICS from their Broadcom contacts and their labs. They would send these shortly after. But even with NICs and a switch we would be unable to use their speeds without a proper 400Gb cable. The only exception to the peripherals were our LIQID IO Accelerators, which we installed into the ADS system.

We also reached out to a couple of other institutions/companies that were recommended to us in some form. MiTAC/TYAN, HPE, possible Asus, the National Research Platform, EVOTEK, Lambda Labs, SuperMicro, and a more that we have lost track of. Understandably, most of them would be unable to help out on such a short notice, or perhaps saw it too difficult to aid us. This was all during an AI boom, after all.

Are you keeping track? We have 2 nodes, a 400Gb switch, no promise of a third machine, AMD will support us but it’s not clear when or how we’ll get hardware, we still need 4xMI210s, still re-speccing out a new system, getting 400Gb NICs soon, still need some kind of cable that supports this speed, don’t forget about our LIQID Honey Badger cards, and most of the team is still transitioning to these machines while they test on the previous cluster resources we’ve had.

In the next month, Michael Woodacre from HPE was able to provide us with a generous 4xMI210s. The turnaround was very quick, and they arrived a few days later. During our installation we realized that the power cables packaged with the system were VHPWR and not the EPS 12V standard that the MI210s need, so we couldn’t even use these. And despite now having 400Gb NICs and a 400Gb switch, we needed to configure it.

Finally, among new email chains we spoke with International Computer Concepts (ICC-USA) for a promise of a final node that could fit the last 4xMI210s, got a loan of 8xEPS12V from Aeon Computing, and spoke with Pivotal Optics, a main cable supplier of SDSC, and their network engineers for a 3x400Gb Direct Attach Copper cable of 3m.

I want you to realize that during this whole time our teams are working on building and testing the software at the same time the system integration is happening in real time. At no point does the system look the same every week.

Now, acknowledging our issues, SDSC has accomodated the team with Express Shipping, and will allow us to ship Monday morning to arrive on Friday/Saturday of our competition. And we have a load of hardware/software support problems.

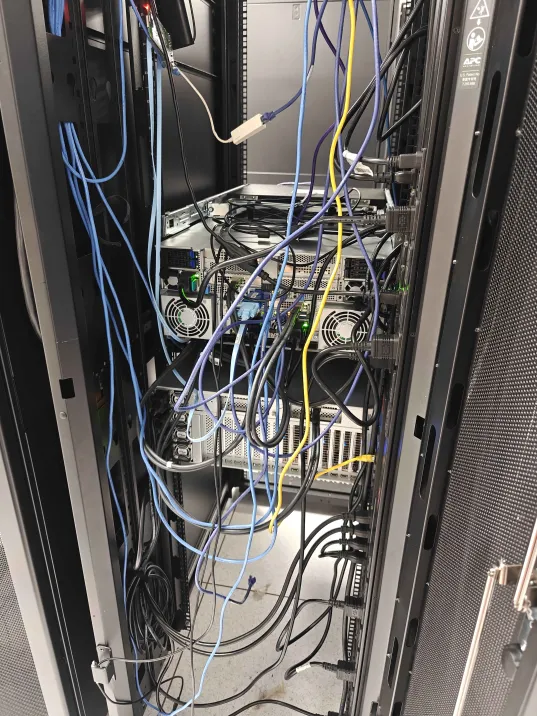

We’ve finally got all hardware of our final cluster, but the AMD GPU BIOS from HPE are different BIOS versions and are set to read only, even with their free firmware tools. We’ve installed the NICs and set up the Switch and followed the instructions online for a manual Broadcom Driver install, but the copper cables are not working, even after going to the bios and correcting the relevant BIOS tools. And we do not have our cluster up working.

Dawn of the Final Week

The flight to Atlanta is Friday, the 15th of November. The date this details is Friday, 8th of November. The express shipping driver has arrived early and he has parked his truck on the loading dock. 3 days until shipping.

The final GPUs and Infinity Fabric Links from AMD show shipping status as of in SD yesterday. They’ve been shipped directly from Taiwan to us. They smell new. Of metal and that slight burnt smell leftover from manufacturing. We integrate these GPUs and their Infinity Fabric Links into the final node and they just work with our benchmarks. It’s almost magical.

We are spending all day at SDSC working. The network is still not setup and the switch is still having some issues. But luckily, Kent Tsui, a Micas Network Engineer, is in San Diego and is willing to help us. At the same time, Wyatt from Liqid also comes to get an idea of our work, show off of the hardware LIQID is working on, and treats the whole team to a meal. So midday Kent comes over and helps us directly in the datacenter. Since we had already went through all of the intiail debugging, he is quickly able to pin the issue down to be due to copper cables, which had not been tested with the networking equipment before. He explains that optical cables expect some sort of port training, a communication between the switch and the NICs to operate on the same speeds and standards. Turning this feature of the NICs off in the BIOS was all we needed. We then just ran some testing:

[mysecretuser@percy bin]$ ib_write_bw -d bnxt_re0 -i 1 -F -R -D 10 --report_gbits -q 3 10.0.0.10

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

RDMA_Write BW Test

Dual-port : OFF Device : bnxt_re0

Number of qps : 3 Transport type : IB

Connection type : RC Using SRQ : OFF

PCIe relax order: ON

ibv_wr* API : OFF

TX depth : 128

CQ Moderation : 1

Mtu : 1024[B]

Link type : Ethernet

GID index : 3

Max inline data : 0[B]

rdma_cm QPs : ON

Data ex. method : rdma_cm

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

local address: LID 0000 QPN 0x2c01 PSN 0xd2cf40

GID: 00:00:00:00:00:00:00:00:00:00:255:255:10:00:00:12

local address: LID 0000 QPN 0x2c03 PSN 0xbd282a

GID: 00:00:00:00:00:00:00:00:00:00:255:255:10:00:00:12

local address: LID 0000 QPN 0x2c04 PSN 0xc9572c

GID: 00:00:00:00:00:00:00:00:00:00:255:255:10:00:00:12

remote address: LID 0000 QPN 0x2c26 PSN 0x356926

GID: 00:00:00:00:00:00:00:00:00:00:255:255:10:00:00:10

remote address: LID 0000 QPN 0x2c0f PSN 0x55318

GID: 00:00:00:00:00:00:00:00:00:00:255:255:10:00:00:10

remote address: LID 0000 QPN 0x2c71 PSN 0x7d7282

GID: 00:00:00:00:00:00:00:00:00:00:255:255:10:00:00:10

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

#bytes #iterations BW peak[Gb/sec] BW average[Gb/sec] MsgRate[Mpps]

65536 4159603 0.00 363.47 0.693268

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Note that a iperf3 isn’t a good test and won’t reach 363Gb. By instead using the ib benchmarks we’re able to test that RDMA is available on these nodes and are also able to reach higher bandwidth since we don’t have to wait for the CPU’s permission.

Going back to our GPU situation, the AMD BIOS on our first GPU system is still different. This seems to be the only reason that occurs to us as to why MLPerf and HPL are failing. By now, we’ve given our AMD contact root access to use his tools to help fix our GPU. We’re in contact with him and he’s helping us debug our issues. When he’s done, we want to attempt the use of the Infinity Fabric Links one last time. They don’t work, but at least the GPUs do.

It’s still Saturday, and the whole team is trying to run their tests. We believe the main compute part of the cluster is complete. There’s still a little more setup to go, and Sunday will be grueling. So the app/benchmarking team takes a rest while our sysadmins continue throughout to keep setting up monitoring, debugging speeds, firewalls, and anything leftover. By the time this is done, it’s already Sunday midday.

I remember coming up to our club space and trying to work on more issues at my desk. I wanted to use every minute. But every couple of seconds I would lose consciousness, only to awake at the sense of my head falling. After this had happened too many times that I had lost my sense of time, I decided to go to sleep. But I was awoken an hour and a half an hour by the team for help. I didn’t sleep again until after the cluster had been shipped.

– Francisco, aka Paco

Setting up the firewall and installation of docker breaks our MPI instance on Sunday. So we finally figure out it’s trying to route MPI processes through an incorrect port and Bryan Chin realized specifying the port or configuring the default solves this issue. When we finally have it working, it’s already midnight. We have to begin tearing down the cluster.

This is a small timelapse of us bringing the machines out of the datacenter and passing through the lobby. In the lobby we are organizing our cables and extra equipment that we can box.

This is what it looked like shipped. We pack everything into a crate and a pallet. The crate holds our half rack and a few bags of our equipment. The pallet a wrapped set of boxes of our nodes and big hardware.

By the time we are done, we bring these into the loading dock to meet the driver at 5:30am.

We ship the cluster at 6am.

Competing

Overview

A picture of the team eating in the arriving airport.

When we arrived we were really anxious to start our setup. Even going beyond what we wished to make sure workked, we had already planned some changes that we had wanted to test. So for Saturday night, when it was ready, we got to work putting the cluster up.

For the rest of Sunday, including the dreaded graveyard shift, it was organized to prioritize benchmarks and the cluster setup. We had wanted to get some kind of monitoring system setup via our RPI, but under such time constraints we were only able to partially achieve this. Furthermore, we did some tweaking to our network to have a firewall as strict as possible, for we are graded on this.

Monday morning, the day of the competition, it seemed something broke once again. This was not great, as we had good runs in our benchmarks the previous night. Additionally, the competition structure was such that we could not verify our benchmark runs for HPL, MLPerf, and the mystery benchmark separately; they all had to be run consecutively. We thus spent a lot of our time fixing the HPL and MLPerf runs, and managed to get HPL and MLPerf runs and a partial targets of our mystery benchmark with less than 2 minutes to spare. When the benchmarking period had finished, they revealed the applications. The Mystery Application was an ML one, Find My Cat. Teams would work to build the best cat recognition model out of a series of images and would find images to test against one another.

At some point during the competition our network had a vulnerability. We were exposing all of our prometheus’s node-exporter data. Now, while at first the firewall didn’t show anything off, this was because the default port for node-exporter was the same as a Rocky Linux default node manager. So, while firewall-cmd didn’t say the name of the port associated with that service, it was the same as node-exporter. So we disabled, and we were dandy.

There was also a period where late into the night we accidentally began running two jobs at once. Luckily, we were able to stop our jobs before the power was recorded 👀. You can see what was recorded in the following image.

Mystery Benchmark

When the judges revealed a “mystery benchmark” on the first day of the competition, it turned out to be NASA’s NAS Parallel Benchmarks, a classic benchmark for measuring parallel performance. The tasks was to run the CG and MG kernels of the benchmark for problem sizes B, C, D and E. We initially felt confident; setting up and running the benchmarks seemed easy enough, many of the optimizations and compiler flags from ICON looked like they would work here as well.

We discovered early on that you don’t just optimize code; you optimize collaboration. Reusing ICON’s optimization flags saved us precious minutes of testing and logging.

In our eagerness to squeeze out extra performance, we used a set of vectorization and optimization flags that had worked in one of our prior ICON build configurations. Unfortunately, one of the fast math flags, specifically the -avx2 flag, led to exploding calculations at large problem sizes. We did not catch this mistake initally, as the smaller problem sizes completed correctly. By the time we did catch it, we only had time to complete a partial run before the window for submission closed.

“There was a lingering sense of loss and frustration at catching a simple mistake too late, and not being able to show our true potential”

– Aarush

Our frustration grew when, a few hours later, we realized that we could have scored better partial performance by organizing our run script to complete multiple small problems first instead of going from small to large problems on each kernel. In limited time, the problem size-based sort would likely have allowed us to have more complete submissions, but the stress of the moment prevented us from realizing this in time.

There’s a very important lesson to take from the mystery benchmark: You can’t sacrifice correctness for speed. Optimizing code is often a balancing act, and one tweak too many and you risk losing the stability you fought so hard to gain. And unfortunately, we were just on the wrong side of that balance at the competition. In the future, we’ll be more thorough with our post-run verifications so that we can catch a failed or invalidated run before it’s too late.

NAMD

The NAMD tasks were fun; they were designed to emulate real scientific research done with the software, and a significant part of the tasks involved scientific analysis. The tasks tested a wide range of our knowledge: there were two physical chemistry simulations, two replica exchange simulations (one of which could only be run using the CPU mode), and a benchmarking challenge that allowed us to change any and every parameter we wanted in order to get the fastest complete benchmark run. These tasks were very different from what we (or any of the teams, really) had prepared for, which fostered a lot of communication with multiple other teams who were very willing to discuss issues and troubleshoot.

From early on, it was clear that we would not be able to finish all the tasks in the given time, as many of the simulations took hours to run. Additionally, our hardware put us at a disadvantage compared to other teams (for example, one of the replica exchange simulations would have taken more than 12 hours to complete for us, compared to 6-8 hours on other clusters). There was a lot of difficult decision-making involved, and incomplete results were submitted for most of the tasks.

Overall, we did the best we could have given the situation, and our results reflected that. Even though our preparation did not directly correlate with many of the tasks, it left us prepared to adapt and tackle each one of them, a fact that was also reflected in our team interview with the application judge (he said that it was we knew what we were talking about!). We submitted the task results with no major issues, with about an hour left in the competition.

ICON

During the competition, the task we were given for ICON turned out to be really interesting: With a time limit of 3 hours, measured with timestamp logging in our output submission file. Within these 3 hours, we had to configure the start and end dates of the ICON simulation for a set of given input files and values. This tested our knowledge of how fast ICON could run on our system, with the parameters we chose. Set a simluation too short, and we waste precious minutes that could have allowed a longer simulation. Set a simulation too long, and the entire run is invalid, wasting 3+ hours.

The 3 hour limit given to us included any set up and initialization tasks. After the run, we had to process the output results and develop a visualization using a tool of our choice. We made slight modifications to a previously built testing script from the fall, and used Python to visualize the output.

In real life, this corresponds to a workflow you might see in a research lab or as part of an HPC task. When you request an interactive node or assign a time limit to your slurm content submission, which is commonly seen for billing and tracking purposes, you have to know how long your run will take. Taken inversely, this means you have to know how much processing can be done by your application in a fixed period of time, including any set up and clean up tasks.

Taming the 3-Hour Limit

We started simple, with a conservative run that finished in slightly more than 2 hours. This was a pleasant surprise. With limited information, we predicted a wide completion window, yet were relieved when it landed near the lower bound. We knew we had room to maximize our potential. Further runs brought us closer to the max potential, but highlighted certain areas for optimization. Our final run was probably the most optimized it could have been given the challenges we had faced from the start. As the run timer got closer and closer to finish, we waited and watched with baited breath: Had we become overconfident, and set up a run that would exceed 3 hours? 2:45 became 2:50 became 2:55…

Had we become overconfident, and set up a run that would exceed 3 hours?

2:56. 2:57. 2:58. Now would be a good time for the program to finish…

2:59. Oh no, we messed this up for sure.

But in a scene straight out of an action movie, like a bomb deactivated with seconds to spare… The run finished in 2:59:48, with only 11.xx seconds to spare. We cheered and let out the breaths we didn’t realize we were holding. Even simulating another minute of the weather likely would have tipped us over the edge. Immediately, we began the quick verification process to make sure all of the files were created and closed correctly. Then, we submitted all of the required files, double- and triple-checking to make sure that nothing was missed.

Although ICON had been hard and full of challenges, at the end, knowing that our final run maximized our time constraint provided a small measure of solace.

Our ICON score had a lot of room for improvement. With a relative score of only 30 out of 100, we lost 10.5 total points here. ICON might have been one of the hardest tasks we were given. It wasn’t easy, but in the end, juggling dependencies, compiler flags, and last-minute surprises made for a deep learning experience that will help inform our approach to challenging applications and benchmarks in the future, allowing us to continue to have strong overall performances at future competitions. We’ll look into refining our build pipelines, and considering a different approach to team priorities in the future.

ICON showed us that HPC is about more than raw computational power. It’s about optimizing software to match hardware constraints while balancing team needs, and this is a lesson we will keep with us.

HPL

Unlike simply running a preconfigured test, the competition required us to fine-tune parameters on the fly to maximize our system’s performance while staying within power constraints. We experimented with different block sizes, process grid layouts, and compiler optimizations to achieve the best possible FLOPS score.

A major challenge we faced was power consumption. When running HPL with Docker, we noticed significant power spikes, causing our cluster to exceed the competition’s power limits. This issue was unexpected and difficult to manage in real-time, as the power draw fluctuated unpredictably depending on how HPL was scheduled across the CPUs and GPUs. We had to quickly adjust our approach, switching configurations and scaling down workloads to prevent the excession of power limits. These power-related struggles put us at a disadvantage compared to other teams who had more stable power-efficient setups.

Given the time constraints, we had to make tough decisions about which configurations to attempt and which to abandon. Despite these difficulties, we managed to complete and submit our results with no major system crashes. Our preparation, while not directly aligned with some of the specific competition constraints, gave us the adaptability needed to troubleshoot and optimize under pressure. The judges acknowledged our understanding of performance tuning and HPC optimization in our team interview, reinforcing that we had a strong grasp of the problem space. Ultimately, we did the best we could under the given circumstances, and our submitted results reflected the effort we put into overcoming the power and performance challenges.

Conclusion

Overall, it was a very fun experience. All of it was. During our disassembly of our cluster most of these pieces had to go back to their respective vendor. So we had to seperate and ship the parts from here.

Final Score Breakdown

Our team won 4th overall!

This makes it the best placement from the US teams for a third year in a row. And this year’s best placement amongst US+European teams.

While a majority of teams use an Nvidia based stack, our team has used the AMD ROCm, a rarity as H100 GPUs going ever so prevelant amongst the competitors in the last years. While last year our team was able to be the first in the world to have MLPerf to run on AMD GPUs, this year we were the first in the world to get multi-node MLPerf working on AMD GPUs.

| Item | unweighted score | weighted score |

|---|---|---|

| Poster 5% | 69.400 /100 | 3.470 |

| Benchmarking 15% | 70.700 /100 | 10.605 |

| NAMD 15% | 54.348 /100 | 8.152 |

| ICON 15% | 30 /100 | 4.500 |

| Reproducibility 15% | 54 /100 | 8.100 |

| Mystery Application 15% | 22.400 /100 | 3.360 |

| System 15% | 95 /100 | 14.250 |

| Scavenger Hunt 5% | 94 /100 | 4.700 |

| Total 100% | 57.137 / 100 |

Takeaways and Thanks

We’d like to extend thanks to the awesome contributions of the entirety of SDSC and CSE at UCSD. Specifically the efforts of our mentors Mary P. Thomas, Martin Kandes, Mahidhar Tatineni, and Bryan Chin. The efforts of our company sponsors as HPE, Pivotal Optics, Aeon Computing, Applied Data Systems, International Computer Concepts, Gigabyte, LIQID, Broadcom, and Micas Networks and AMD. The UCSD Supercomputing Club would never have grown and accomplished as much without your help, and we are grateful for all of it.